The U.S. Sets Its Sights on Asia

Over the past decade, the Asian-Pacific Region (APR) has shown impressive rates of economic growth and has had some success in reducing poverty. Yet many experts are talking about the displacement of the centers of power and economic life from Europe to Asia. China is playing the role of regional leader, while the U.S. is attempting to strengthen its influence in the region, including through a new integrated association known as the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Politics in the APR occupies an increasingly important place in U.S. foreign policy, with particular emphasis currently on the new bloc which plans to create free-trade zones across the entire region. The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) is without a doubt one of the Obama administration’s main priorities and offers an alternative to the Chinese project, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which is also in the negotiations stage.

WEJ spoke with several international experts about the distinctive features and advantages of the TPP. According to Henry Nau, Professor at George Washington University, “The TPP and its European equivalent, the TTIP, are currently at the core of global trade policy. Concluding these agreements is important in part because the WTO Doha Round is in a deep crisis. Therefore the main advantage of the TPP is its ability to bring together Japan and the NAFTA countries – Mexico, the U.S., and Canada. If it happened, it would help to get China’s attention and perhaps agreement on more free trade terms than those represented by RCEP.”

Susan Aaronson, Researcher of International Relations at George Washington University, commented on the remarkable nature of the TPP, saying, “The main advantage of TPP is that it binds countries which work together in supply chain units for many products. But TPP is a comprehensive trade agreement it covers a wide range of traditional sectors governed by trade agreements already such as services, tariffs, and non-tariff trade barriers with new sectors (such as investments and e-commerce) and new rules on regulatory coherence, transparency, and privacy. It is called a 21st-century agreement because it is so comprehensive.”

To date, 12 countries are involved in the negotiation process for creating the TPP; they make up nearly 40% of the global GDP and 26% of global trade. If the parties are able to find a compromise and an agreement is reached, the TPP will become the largest free-trade zone in the world. As the largest economy, the U.S. (with 75% of the total GDP of the prospective members) is undoubtedly dominating the negotiations. Other countries participating, in order from the largest economy, include Japan, Canada, Australia, Mexico, Malaysia, Singapore, Chile, Peru, New Zealand, Vietnam, and Brunei. South Korea is also interested in joining, which would significantly increase the weight of the TPP.

The U.S. already has bilateral agreements that eliminate customs barriers with several of the organization’s future members. According to Joseph Pelzman, Professor of Economics, International Affairs and Law, George Washington University: “In fact, six of the countries already have FTA agreements with the US.- Australia, Canada, Chile, Mexico, Peru, and Singapore. The countries that make up the TPP negotiating partners include advanced industrialized, middle-income, and developing economies. While it is possible to argue that there may be trade creation among the participants with whom the United States presently does not have FTAs, the greater value of the agreement to the United States may be in establishing a new trade policy “template” covering non-trade related issues that can be adopted throughout the Asia-Pacific region.”

Scott Miller, Senior Advisor at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, explained to WEJ the role of the TPP and the changes included in the agreement for participating members who already have bilateral free-trade pacts with the U.S.: “TPP is intended to improve existing trade arrangements among the parties by extending product coverage and broadening scope. For current US FTA partners like Chile or Australia, TPP includes new areas (SOEs, digital trade). Also, several TPP parties (importantly, Japan) have MFN trade with the US, meaning there is a lot of new market access to be gained.”

As we see, the initial makeup of the TPP doesn’t include many of the largest Asian economies (such as China or India) and is being viewed more as a prelude to a much wider economic integration, covering most of the APR. Overall, the region makes up 60% of worldwide GDP and more than 50% of global exports, which opens up great potential for further expansion of the TPP. Hoping to expand the Asian free-trade zone even further, Barack Obama even invited China to participate in the project. However, Beijing seems more interested in developing its own structure for integration.

In reality, the TPP is an ambitious attempt to create a comprehensive agreement that will not only lower tariffs and other barriers to open markets, but also implement standards across a wide range of issues that affect trade and international competition. A large portion of the negotiations deals with issues surrounding the rules for intellectual property rights, state procurement, and the role of the government in private enterprises. The preliminary version of the agreement has 29 chapters devoted to a wide range of issues, from financial services to telecommunications to sanitation standards for food production. Some provisions of the agreement require substantial changes to existing laws and standards in member states. Specific and exact formulas that are being looked at by those participating in the negotiation process aren’t fully known. Negotiations are taking place in secrecy and the press and international community must be content with the information provided by official delegations and material that accidentally finds its way online.

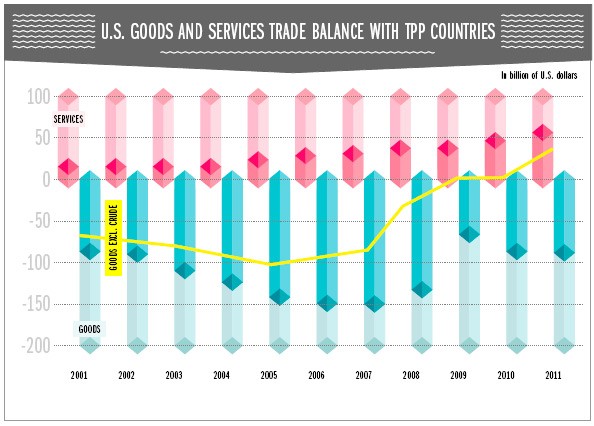

Most analysts view trade liberalization as a stimulus for economic growth. As for how the TPP will benefit the U.S., in addition to increasing its influence in the region, the agreement has the potential to increase American exports and investments due to lower tariffs and ensure equal conditions for large or fast-growing markets. In addition, increased exports, in theory, should lead to growth in domestic manufacturing, and consequently the creation of new jobs and increased GNP. According to the White House, the TPP will contribute to the creation of new jobs in the U.S., and by 2025 will provide an additional $123.5 billion annually in American exports.

The Peterson Institute for International Economics assesses the future benefits as follows: If current participants remain the same, the U.S. will gain $78 annually; in the most extreme scenario, the free-trade zone will expand throughout the Asia-Pacific region and the U.S. will gain $267 billion annually.

Like any other multilateral trade agreement (just recall the never-ending WTO Doha Round), the TPP has been fraught with difficulties. Each country participating in the negotiations process has a number of products that it wants to protect. The U.S. is trying to gain access to Japan’s powerful agrarian sector, specifically its rice market. Australia and New Zealand want special preference for their milk products, and Vietnam wants preference for its textiles and shoes. In addition to automakers, American sugar and textiles producers are expressing concern over increased foreign competition.

So far, conflicts between parties have yet to be settled and the timeline for the TPP to come into force remains unclear. There is controversy, for example, over the need to reduce support to businesses, private or fully state-run, in order to promote competition with the private sector. Professor Pelzman thinks that “The US negotiating position with the agricultural sector is defined by a single issue – market access to its exports. US agricultural trade with Mexico and Canada, the largest TPP negotiating partners, is currently duty-free. Consequently, the US position with respect to non-FTA members such as Brunei, Malaysia, and Vietnam will most likely involve market access to US exports of processed foods and cotton. The two US outliers would be dairy and sugar who would prefer not to negotiate market access for fear of additional competition from New Zealand and Australia. The major market that US negotiators will likely push to open will be Japan, which maintains the largest barriers to US agricultural exports.”

Experts differ in their estimates of the TPP agreement deadline. “Prospects for the TPP, in my view, are very ambiguous,” says Professor Nau. “Prospects for TPP are questionable,” says Professor Nau. “Not only would the agreement require significant reforms in Japan (for example, agriculture) but there is little support in Washington for nee free trade agreements. Obama has little credibility on Capitol Hill and has not included Congress in the TPP negotiations. In the past, that was the prerequisite for Congress to grant trade promotion authority. My guess is that TPP is unlikely this year and has no better than a 50-50 chance after that. TPP will most likely conclude in 2015 and enter into force in 2016 or 2017”

Text: Olga Irisova

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.